The first time I heard about the ancient city of Gournia, was when an American Lady sat on my front doorstep and cried.

She had been attempting to drive along our street in Kritsá - without realising it wasn’t suitable for cars. Just past our high front step, the street narrows, the walls of the houses close in, and the cobbles give way to steps that lead down to the village’s ‘Big’ church.

When she tried to remedy her mistake, the woman caught the front tyre of her car on a rock - which burst with an explosive THUMP. The car became stuck between the corner of the old ‘kafenio’/coffee shop and a handrail. Only one of our Greek neighbours, seasoned in the art of intricate manoeuvring in Kritsá’s tiny spaces, could coax the vehicle out again - while a black cluster of elderly village ladies gathered gleefully to watch, humming like bees.

The American Lady sat on our high front step, wept embarrassed tears, and drank tea while I reassured her that she wasn’t the first - and probably wouldn’t be the last - driver to get stuck. When she finally collected herself, she told me that this was her first sightseeing trip in Crete. She was going to be on the island all summer, living along the coast in Pachia Ammos, while her husband worked as an archaeologist at the ruined Minoan city of Gournia.

I’d glimpsed the sign for Gournia when I’d been travelling along the north coast on the National Road - an ancient place where geometric, crumbling stone walls were packed tightly together like a maze in a puzzle book, but I hadn’t yet stopped to visit. Mentally, I added it to my list of places to explore.

When I made my first visit, I discovered that Gournia is one of those magical places, where time slows as you enter, and flows more gently than it does beyond the rusty perimeter fence. The ruined Minoan town, dating from between 1800-1500 BCE, sits on a small, rosemary-scented hill overlooking a deep, turquoise bay. The remains of two-storey houses and cobbled streets spread from the base of the hill up towards a central court and ‘palace’ at the summit. Radiating down towards the sea on two sides, are artisan quarters where workers crafted what the city needed from bronze, clay and stone - pot sherds are still easy to find everywhere. A few metres away are the remains of a harbour, where ceramics, jewellery and weapons were loaded onto boats to be traded throughout the ancient world. Minoan goods are amongst the many treasures excavated in ancient Egypt.

Sitting in the peaceful, open court at the top of the site, early in the spring when pink and purple anemones stud the ruined cobbles, it’s easy to tune out the few cars on the National Road below - and picture offerings being made to a goddess of fertility. I’ve imagined craftsmen hammering in their workshops, the sound of children echoing in the narrow streets as they ran to the sea - the bustle and life of a place that must have been as thriving three-and-a-half-thousand years ago as Agios Nikolaos is now.

I’ve contemplated what Minoan life - and love - and society - must have been like in Gournia many times since that first visit, but I never spared a thought for the time when the city was re-discovered - until a few weeks ago...

On an ice-blue winter morning in the UK, I switched on BBC radio by chance and found myself listening to a debate about whether woolly mammoths should be recreated from ancient DNA1. As the programme ended, Dr. Tori Herridge, the evolutionary biologist who had been leading the discussion, described the pioneering scientists who inspired her career. To my surprise and delight, the name Gournia arrived as unexpectedly as that American Lady on my doorstep. One of the academic’s heroes was the American woman who re-discovered Gournia in 1901 - the first woman ever to head an Aegean archaeological excavation.

Harriet Boyd graduated from the American School of Archaeology in Athens in 1897 at the age of 26, and hoped to join a dig in Corinth. Overlooked because of her sex and frustrated at the lack of opportunity, she volunteered to be a nurse instead when the Greco-Turkish War broke out. Boyd worked at the front at Thessaly, travelling on mules, sleeping rough and learning Greek for nearly three years. When the fighting eased, she travelled to Crete looking for a way to use her academic knowledge at last, and met the keeper of Knossos, Arthur Evans. Impressed by her fortitude - and the hardiness that must have been good training for an archaeologist - Evans advised her to search for a site of her own in the East.

Boyd made inquiries in the villages along the coast, and then began to excavate around the village of Kavousi, where the discovery of an intact Bronze Age ‘Beehive’ tomb in 1900 helped to give her professional credibility. Later that year, Boyd was shown to another low hill nearby, by Vassiliki schoolteacher Georgios Perakis. As she began to dig, Boyd discovered pottery - a goddess figurine and a double-headed axe. Before long, she realised that what she was uncovering was no less than an entire Minoan town. By the end of 1901, The Times of London was heralding Gournia as ‘The site best worth visiting’ in Crete.

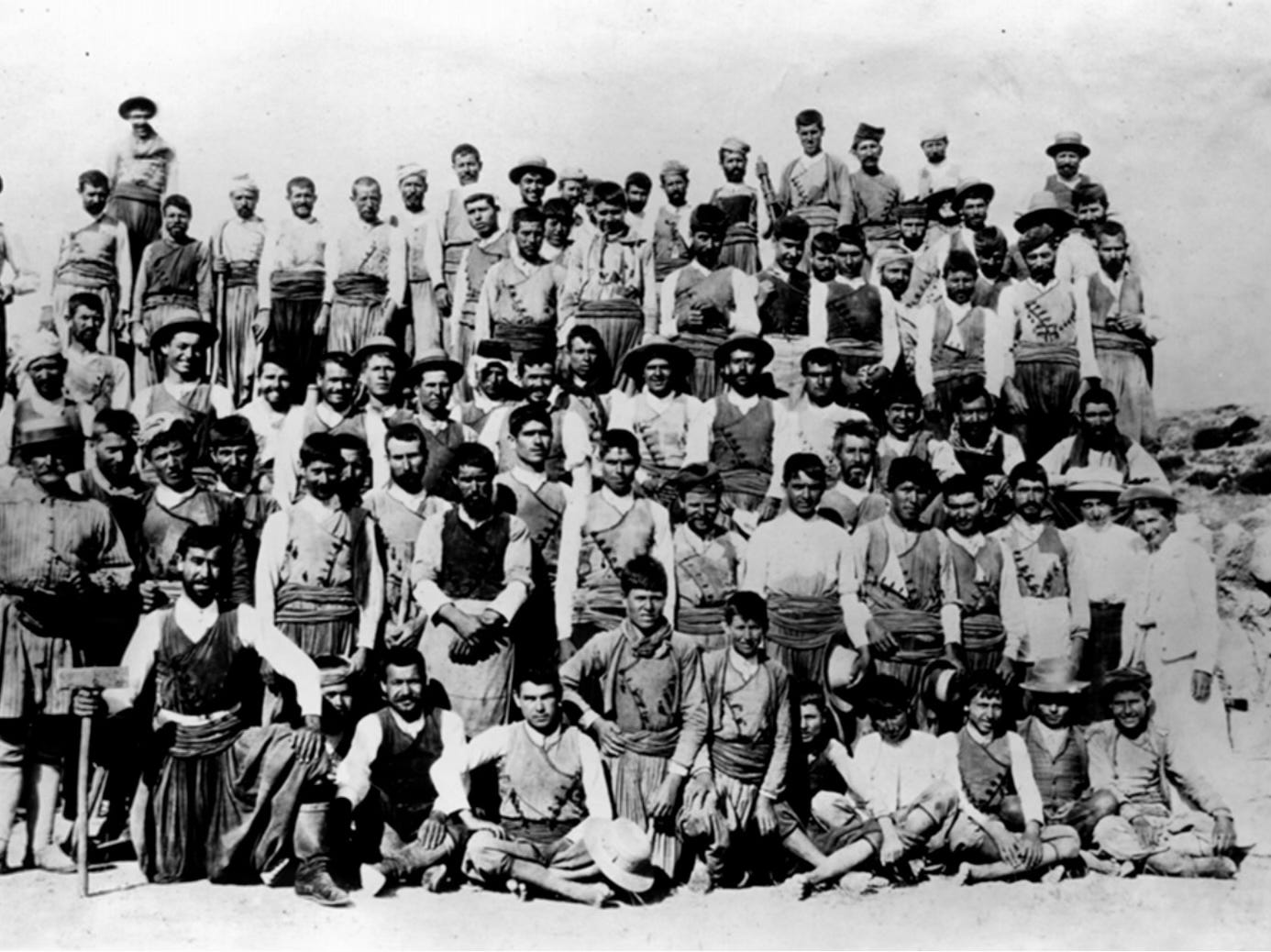

Over the summer digging seasons of 1901, 1903 and 1904, Boyd headed up a workforce of one hundred men and was joined by two further pioneering archaeologists, Edith Hall and Blanche Wheeler. As the site grew into new trenches and excavations on the coast, Boyd attributed some of her success to being able to integrate with the female side of Greek village life. Stories of unusual finds and new potential places to dig were shared by the women with whom she worked and lived. She and her female colleagues were accepted into family circles, were called on to use their medical knowledge at births and deaths - and became bridesmaids at local weddings2

But while archaeologists like Arthur Evans and George Pendlebury are forever associated with Knossos - (you bump into their names in almost every guide to Crete, and on display boards at the famous site) - you won’t find Harriet Boyd’s name - or the names of Hall and Wheeler, recorded anywhere in the guidebooks, nor on the ground.

Now, when I go back to Gournia, I know I’ll be imagining all the layers of history of this place - the social life of an ancient community, the working camaraderie of an excavation at the dawn of the new era - and the centuries of stories between, shared by women that have kept their memory alive.

Without two American women arriving in my life unexpectedly, I might never have discovered Gournia at all!

If you enjoyed Claire in Crete, you may also like my short story, Ann Hilder - a mystery inspired by the work of the artist LS Lowry and his shadowy muse.

Ann Hilder is available as a paperback and ebook on Amazon at https://amzn.eu/d/bMidwmh

‘Claire In Crete’ publishes new articles every two weeks. It’s free to subscribe, and this post is public so please feel free to share it.

Thank you for reading!

The moral conclusion of the discussion was ‘no’ - recreating a mammoth would involve unnecessary experimentation with modern elephants.

An introduction to more information about Boyd is on the ‘Trowelblazers’ website, which seeks to celebrate the contribution women have made to the fields of archaeology and palaeontology and ensure their names are not lost to history. Evolutionary Biologist, Dr Tori Herridge, is one of the founders: https://trowelblazers.com/2014/04/29/harriet-boyd-hawes-bold-brave-and-bloody-brilliant/

What a brilliant article about three remarkable women, Claire. Thank you s-o-o-o much for holding history's mirror up to these three pioneers of sticking to the facts that archaeology reveals. Schleimann and Evans were diverted from excavated reality by the fame of self-mything a fictionalised Minoa. They had the help of inherited affluence and credulous reporters. Harriet Boyd Hawes, Edith Hall, and Blanche Wheeler would have none of it. They pushed through the barriers of sexism to present archeology as fact, not fantasy. And thank you, too, for so many pictures of the stone walls and hillocky lanes of Gournia under the brilliant sun. Your article painted such a vivid picture I could smell the herbs and bask in the afternoon sun. More please!

What a fabulous story. I'm delighted you have unearthed another unsung heroine.