The Battle of Crete ended with a desperate Allied scramble over the White Mountains to the tiny beach at Hora Sfakion in May/June 1941. In May 2024, I decided to take my Great Uncle, Royal Marine Harry Palmer, back there…

This article was first published in the history magazine of Greece’s Kathimerini newspaper Σελιδες Ιστοριες Jan/Feb 2025. It appears here in English for the first time to mark the 84th anniversary of The Battle of Crete

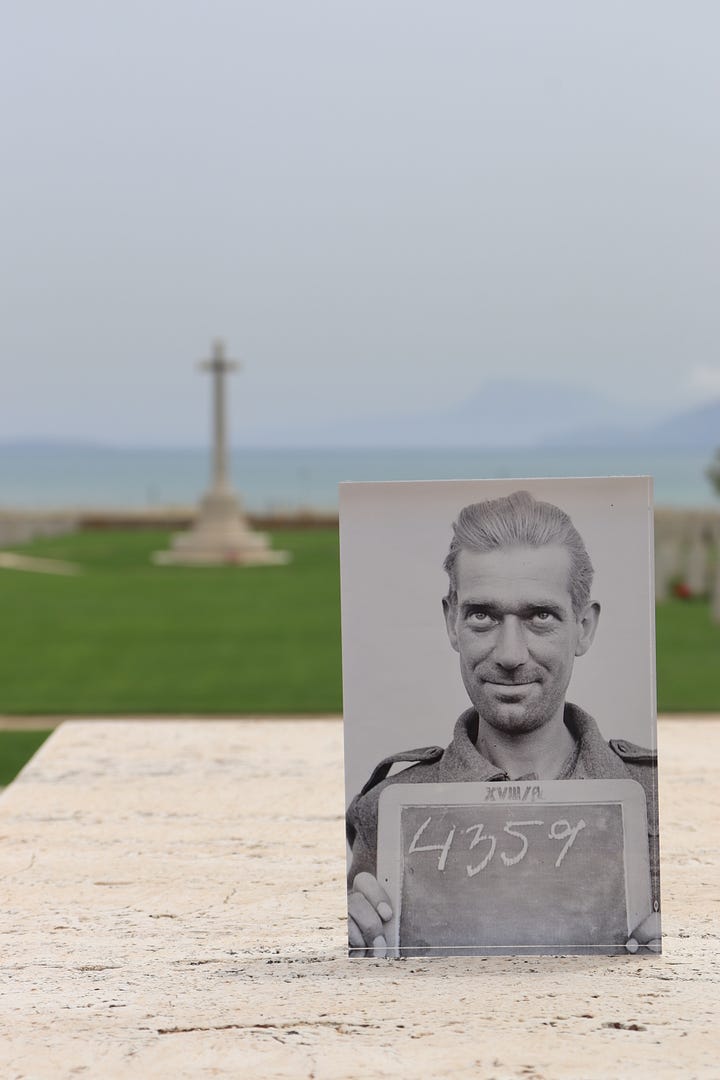

Just two other people are walking amongst the neat rows of graves in the Allied War Cemetery at Suda Bay, Crete, when I arrive on a bright May morning. Hundreds of simple white headstones stand bold against the pure blue sky, and the feathery flowers of Gaura ‘butterfly bushes’ are flaming pink against the cemetery’s white stone walls. I’m here to mark the anniversary of the Battle of Crete – a pivotal moment of the Second World War – and to begin a quest following in the desperate footsteps of one man - my Great, Great Uncle, Royal Marine, Harry Palmer.

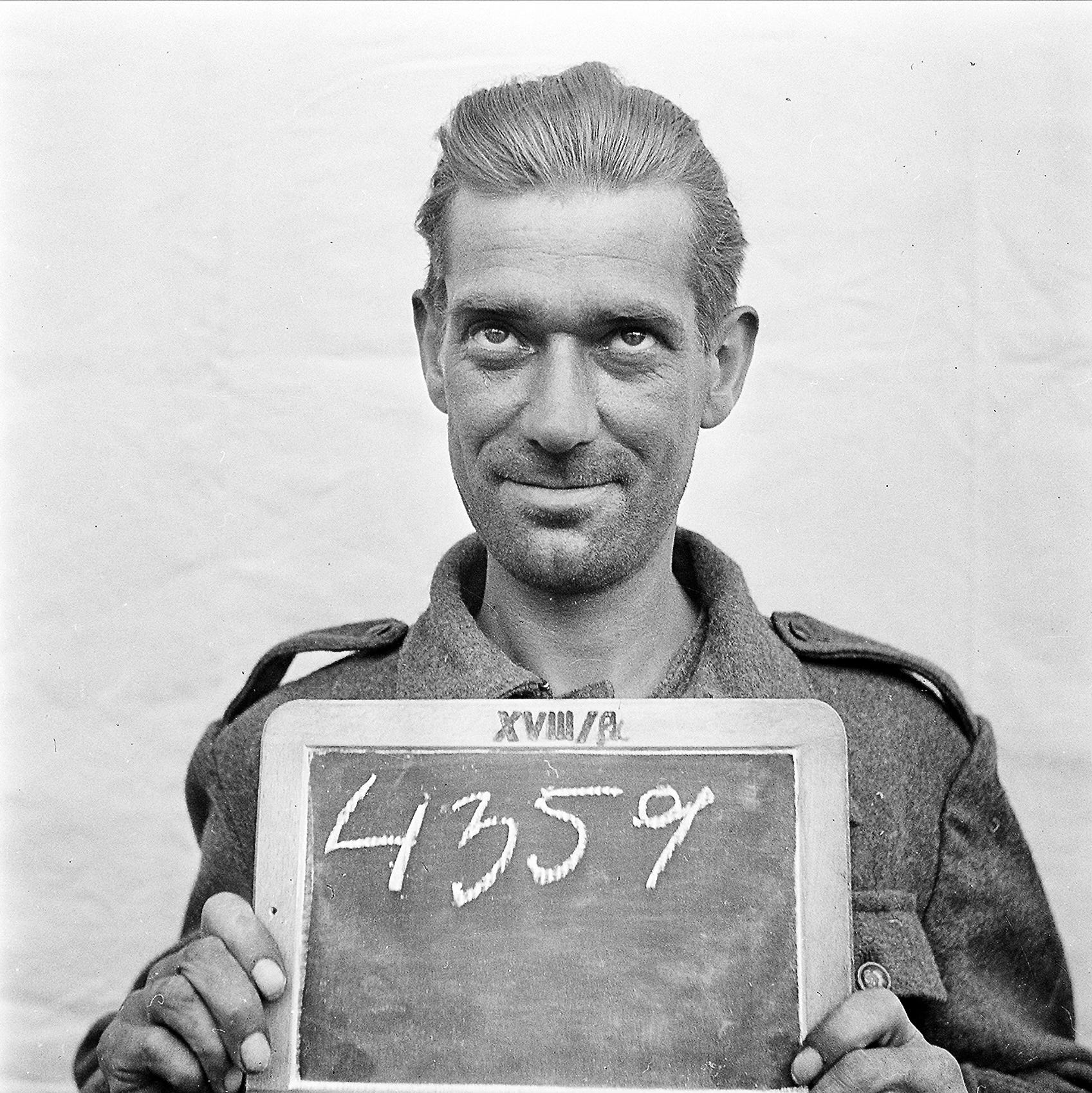

I’ve travelled here with the only photograph I have - a black and white portrait of Harry in uniform, holding a blackboard with the number 4359 scrawled on it. It’s a photograph discovered by my sister, Louise Wade, in the archive of The Natural History Museum of Vienna after painstaking research. Somehow, Uncle Harry summoned the ghost of a smile on the day this picture was taken, and that expression is deeply affecting, because I have learned that it was taken as he entered Stalag XVIIIA in Nazi Occupied Austria - as a Prisoner of War.

Harry Palmer’s journey to that place began in Suda Bay on 20th May 1941, where he had been stationed for just a few days when the Battle of Crete began at 6am. The German bombing raid westwards along the north coast was a little earlier that day than it had been on previous mornings, and so, many of the Allied troops were still eating breakfast when the cloudless sky darkened with German aircraft, tapered-winged gliders, and then with wave after wave of the eerie, blooming shapes of Paratroopers.

By the end of the first 24 hours of battle there were heavy casualties on both sides. It’s agreed now that the invasion could have been ended by an Allied counter-attack at Maleme Airfield, but somehow, with garbled communications and a commanding officer intent on keeping forces back, ready to counter a second invasion force from the sea - which never arrived - by the second day, the Germans had taken control at Maleme and established a ruthlessly efficient air bridge to land more troops.

Harry Palmer, a bookish 34-year-old, who read Shakespeare and Balzac when he was not employed as a painter of ships and houses, found himself fighting along the Suda coast, and on into Canea (Chania) when his company, ‘S’ Searchlight Battery, was hastily reorganised as an infantry platoon. For several days, heavy air attacks meant they could not sleep nor rest – and by May 25th, hungry, thirsty, and under constant strafing from the enemy, they were ordered to withdraw and join thousands of New Zealanders, Australian and Greek troops scrambling over the pass between the towering peaks of the White Mountains. Their goal was the barren south coast, where Royal Navy ships were steaming to pick them up.

It was a desperate, headlong flight of more than 70 kilometres over terrain that shredded army boots, and under a blazing sun that blistered Harry Palmer’s back. The route wound through the Apokronas foothills to the cool, riverside village of Vrysses, then on up over rocks to the Askifou Plateau, before heading towards the tiny shingle harbour at Hora Sfakion. There was only one problem. Even though British forces had already been in Crete for 6 months, the road to Hora Sfakion had never been completed. It ended 3 kilometres short of the Libyan Sea, and a dizzying 500 metres above the beach.

A corridor was established down from the cliff edge – a treacherous path of loose stones and dusty earth, strewn with discarded possessions, and heaving with men, some wounded and carried on make-shift stretchers. When that route became overwhelmed, the vertiginous goat track skimming between the steep cliffs of the Imbros Gorge became a second lifeline to the sea.

Over four nights the Royal Navy evacuated 6,000 troops, with officers given priority so that they could re-form units in Egypt. Unluckily for Harry Palmer, an ordinary British Marine in the rear-guard of the action, he was not one of those taken aboard. As the Germans encircled Allied positions on 1st June 1941, the men of ‘S’ Searchlight Battery were amongst the 5,000 soldiers left behind and ordered to put themselves into German hands. Then, to add insult to injury, the ragged, thirsty climb of the previous days was re-enacted in reverse, as the troops – now prisoners of war – were marched back across the mountains to an internment camp at Galatas.

Recreating the journey by car with Harry’s photograph beside me – first along the National Highway from Suda, and then over cracking, asphalt mountain roads, I think how terrifying it must have been, to be pursued by troops and bombers through such naturally hostile terrain.

In a brief stop at a shady bakery on the Askifou Plateau, rifle fire suddenly, shockingly, clatters out from one of the mountain shooting ranges above the road. As it reverberates around the skyline, I wonder if I have done the right thing bringing Uncle Harry with me. How would he have felt coming back?

I spend the night in Hora Sfkaion, visiting the war memorial, listening to the chatter of many languages in the brightly-lit tavernas that cluster around the tiny harbour. Then, in the morning, I board a shuddering car ferry to Loutro - a brief respite from my pilgrimage.

Although I have been steeped in this history for weeks, putting together troop movements, checking and re-checking the route taken, I haven’t talked to anyone here about it - until the young, wiry manager of the beachside bar where I stop for iced coffee, a chin strap dangling limply in the heat beneath his straw hat, asks me why I am travelling alone.

I tell him I’m not alone. I’m travelling with Uncle Harry - and as I bring out the photograph and lay out the history for him, he listens in astonishment, and then tells me about his own exodus from Syria. It’s the tale of another desperate journey that has ended in another bright, pure place, where flowers blaze pink against white walls - and I reflect, like William Faulkner, that the past is never dead. It is not even past.

The Battle of Crete was fought between 20th May and 1st June 1941. The German invading force met with such fierce resistance from both Allied troops and the local population, and there was such a heavy loss of life, that Hitler declared an airborne invasion would never be attempted again.

A further 600 Allied soldiers escaped from Crete between June and September 1941 - many sheltered by Cretans.

Harry Palmer was a prisoner of war from 1st June 1941 until 26th April 1945. Two of those years were spent in Blechhammer, a sub-camp of Auschwitz. He finally made it home to Manchester, after The Long March. He died in 1965.

If you enjoyed Claire in Crete, you may also like my short story, Ann Hilder - a mystery inspired by the work of the artist LS Lowry and his shadowy muse.

Ann Hilder is available as a paperback and ebook on Amazon athttps://amzn.eu/d/bMidwmh

‘Claire In Crete’ publishes new articles every two weeks. It’s free to subscribe, and this post is public so please feel free to share it.

Thank you for reading!

My parents were from villages above Chania. During the Battle of Crete, Nazis went through my father’s village and executed all the men while the women and children watched in horror. My grandfather was the first to die. The Nazis committed atrocities in the villages of Crete, not only killing innocent civilians, but also burning houses as well as olive and orange groves, the Cretans’ source of income.

Thank you for this personal story. We’ve visited Hora Skafion on the way to Loutro and stopped at the memorial there and another on the road back in a village that was gunned down during the occupation. It fills me with visceral horror and I’m always humbled by the bravery of troops and locals during that time. He was a handsome guy your uncle and I hope he made a good life for himself somehow. I had an uncle held prisoner of war in The Congo - there was a film eventually about his troop - Jamie Dornan, The Siege of Jadotville. These people were ignored by their government for years and my poor uncle never really recovered his mental health. Thanks for this writing, I’m very moved by it.

On a lighter note, what a wonderful restaurant/taverna you have in kritsa now - Thymisi. Visited at the beginning of May, loved it. Looking forward to outdoor visit soon. 🩷