There’s a heart-stopping moment just before any small aircraft comes into land, when it’s completely at the mercy of the wind. Come in too high, or too fast - catch a gust that tips the plane off balance - and what should be a smooth landing can suddenly become an emergency procedure - a ‘go around’ - where the pilot must ‘power on’ to climb, readjust and try again.

The first time I had to perform this emergency move was on a grey, blustery day above Staffordshire, UK, when I was both too high and too fast to land safely. In fact, I had to manoeuvre my little two-seater Cessna to ‘go around’ twice - only landing on the third attempt, when my foot was already shaking on the rudder pedal. I scared myself so badly, I didn't fly solo again for three months!

I’m thinking about that day as I’m sitting at the Plaka end of Elounda Bay, beneath the mountainous Agios Ioannis headland where wind turbines rake the sky. The wind is blowing full in my face, relentless and wild, raging from the causeway at Schisma Elounda past the former leper colony at Spinalonga Island. It’s no place to be on a stormy day, the wind whipping water spouts up out of the sea as it howls and moans, and I’m considering how terrifying it must have been to land an aeroplane on the sea here, as the pilots of Britain’s Imperial Airways did several times a week between 1931 and 1939.

In the 1930s, Elounda was an important point on the map - the crossroads of the world - as Imperial Airways carried mail and passengers from Great Britain to the outposts of empire - to Alexandria, India, South Africa, the Far East and Australia. The mail was essential cargo. Ten million letters and packages were carried annually. The passengers - statesmen, diplomats, military personnel, journalists and adventurers, were merely additional revenue for the airline. They travelled in romantic comfort in a passenger cabin that resembled a first class train carriage. Then, while the plane was being refuelled, or repaired, or while bad weather passed over the Cretan mountains, passengers dined aboard the airline’s tender ship, MV Imperia, which was anchored in the bay, or ashore at the Imperia Taverna in Elounda.1

There were days when storms made landing highly dangerous and planes were delayed or re-routed to Souda Bay at the Western end of the island, but Imperial Airways’ worst disaster happened on an August day when its passengers and crew might have expected the weather to be calm.

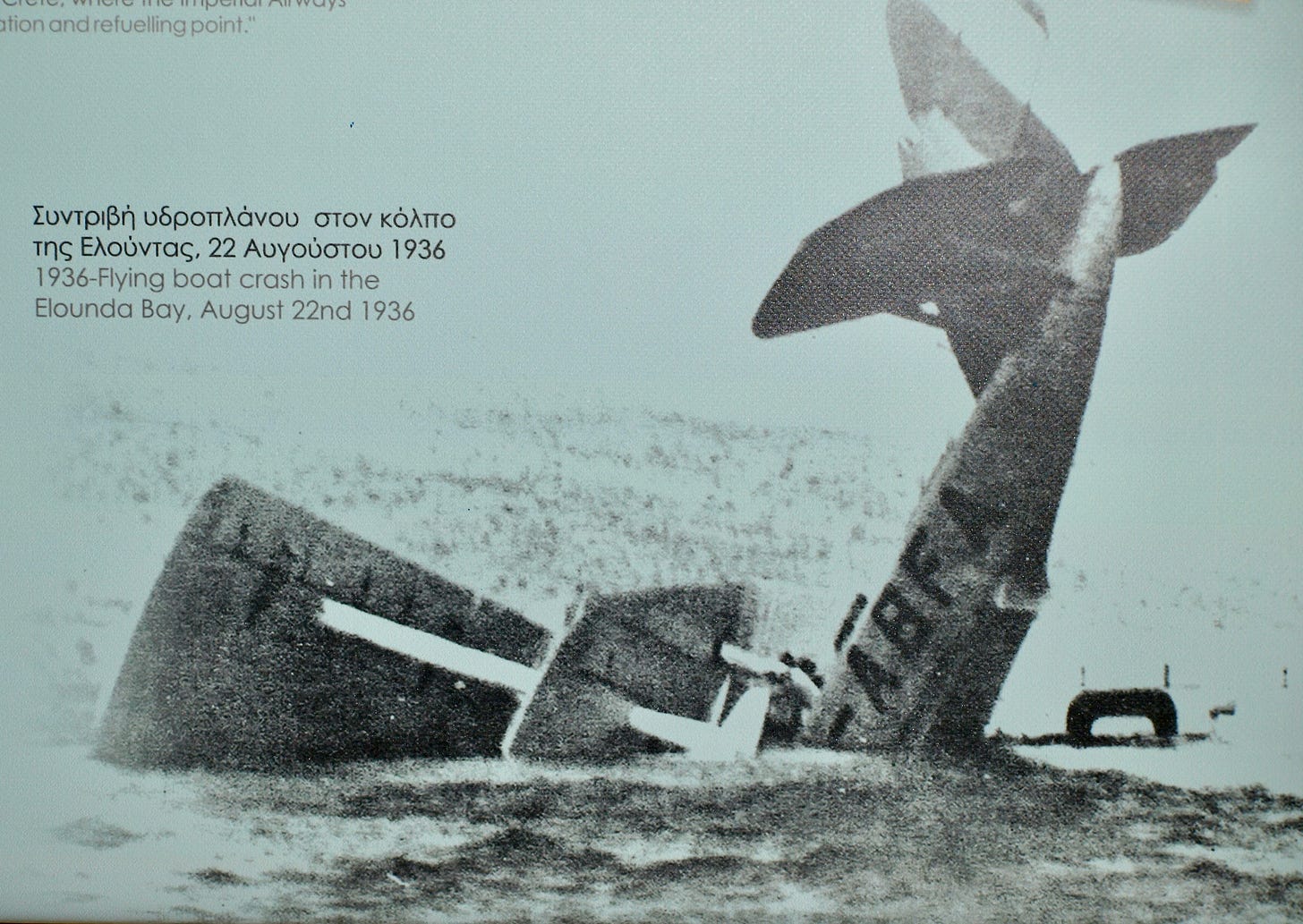

On Saturday 22nd August 1936, the Scipio flying boat was on the middle leg of its flight from Delhi to London via Alexandria. It raced north over Crete from Ierapetra to Pachia Ammos and then along the coastline past Agios Nikolaos, before making its approach to Elounda.

No one knows exactly what caused the plane to nosedive. Some newspapers reported that an SOS was sent shortly before landing, reporting engine trouble - but there was also testimony that ‘the wind was gusting sharply’2 - and a secret cargo of gold may have shifted, setting the plane off balance.

Scipio ploughed into the sea nose first, flipped over and then broke apart, scattering debris across the bay to the shoreline. Two passengers were killed. Four crew members and five further passengers were injured - the worst affected, swiftly transported to Athens for treatment. The dead, both military personnel returning from service overseas, were buried in the churchyard at Agia Triada in Mavrikiano the following day.

After the crash, Imperial Airways continued flying into Elounda in larger, more reliable Shorts Empire flying boats, concentrating on their airmail operations - until the outbreak of war in 1939 made non-military air travel over the Mediterranean impossible. But the presence of the airline in Elounda in the 1930s was an essential part of the village’s development, ensuring that a new road was built from Neapoli over the mountains via Pines to the coast, and offering the local population employment in occupations other than farming, and carob and olive oil processing.

In Dave Davis’ book Imperial Airways in Elounda,3 diary entries written by Francis Pool, the captain of the airline’s support vessel, MV Imperia, describe everyday life in 1930s Crete in all its colour and drama. Pool wrote about arranged marriages and elopements, medical emergencies and a lack of doctors, visiting archeologists and their glamorous wives - traditional Cretan dress contrasting with their northern European fashions.

Pool also described a time when orphans from Neapoli were brought to the coast for holidays, when telegrams containing only a handful of words cost as much to send in drachma as a lunch at ‘The Caprice’ in Chania - and when the Leper Colony at Spinalonga was still a settlement and a community.

Entries in 1938 gradually took a darker turn as war gathered on the horizon. When the war came, Pool joined Britain’s secret Special Operations Executive (SOE), plotting naval missions from Alexandria to rescue Allied soldiers stranded after the Battle of Crete. His success resulted in him being awarded the DSO and an OBE.

These days, if you want to experience the feeling of flight above Elounda Bay, you only have to drive over the headland from Ellinika to see the spectacular view laid out before you, and imagine descending to a landing strip of water the colour of a kingfisher’s back. Or you can climb the trails to the rocky summit of Mount Oxa, 420 metres above sea level, where the birds-eye view reveals the darker waters of the salt pans in sharp contrast to the ultramarine waters of the lagoon, and makes it possible to spot traces of the lost, ancient city of Olous beside the causeway. In the other direction across Mirabello Bay, the long coast shimmers in a luminous crescent all the way east towards Sitia.

When my husband Craig and I climbed Oxa a few days ago, we couldn’t help being reminded how far the elements influence everything here. The mountain landscape is treeless, strewn with scree and prone to rockfalls. Caves have been chiselled into cliffs over thousands of years. Far below, the wind dictates where the Spinalonga tourist boats are moored in the winter, where developers site their hotels and where millionaires buy their houses. Watching kite surfers skimming fast across the waves while the wind did its best to sweep us off our feet, I was back to thinking how dangerous it must have been to land a plane in this extreme, romantic place.

In Elounda Bay, the wind will always be in charge.

If you enjoyed Claire in Crete, you may also like my short story, Ann Hilder - a mystery inspired by the work of the artist LS Lowry and his shadowy muse.

Ann Hilder is available as a paperback and ebook on Amazon at https://amzn.eu/d/bMidwmh

‘Claire In Crete’ publishes new articles every two weeks. It’s free to subscribe, and this post is public so please feel free to share it.

Thank you for reading!

I believe The Imperia Taverna which had some artefacts from Imperial Airways is now permanently closed. However, this archive video of the Imperial Airways service in Elounda, filmed by amateur photographer, Ruth Stuart, in 1931, gives a contemporary flavour of an important airline route. Pictures of Crete begin at 4:45

From the excellent book Imperial Airways in Elounda During the 1930s, by Dave Davis

Dave Davis’ book is usually available from the bookshop on the square in Elounda. Although it isn’t yet available there this month, I’ve been told it will be back on sale during the season.

What a wonderful, informative piece, Claire! One of your very best. I knew nothing of Elounda's role as a hub in the history of intercontinental air transport. Commercial flying must have been an ordeal in those days by our standards. Low altitude, slow as syrup, the noise must have been deafening given the size of those propellers and proximity to the cabin. Your Cessna must be like flying on silk compared to the 1930s. And the last half of the video was a revelatory portrait of Cairo back in the days when camels outnumbered autos. I could practically smell the spice markets and hear the chaffers of the hawkers and braying camels. =Doug & Elysoun

Absolutely fascinating! I’m reading Edward Lear’s journal of his trip to Crete in the 1860s, and it’s amazing to think how things changed in the next 70 years!